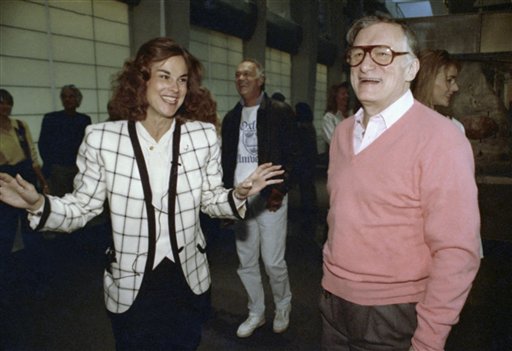

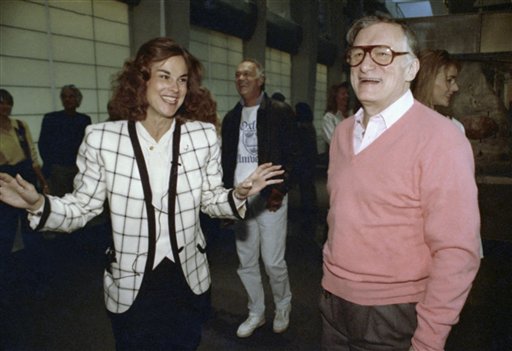

Playboy founder Hugh Hefner tours Playboy's new corporate headquarters with his daughter, company chairman and chief executive officer Christie Hefner, left, in 1992, Chicago. In 2000, Hefner's Playboy Entertainment Group won a First Amendment case at the Supreme Court, overturning a broadcasting regulation that prohibited cable television providers from showing sexually-oriented programming, such as the Playboy Channel, except for between 10 p.m and 6 a.m. (AP Photo/Mark Elias)

In United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group, 529 U.S. 803 (2000), the Supreme Court held that section 505 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 violated the First Amendment because it restricted speech based on content and there was a less speech-restrictive alternative available to protect minors from harmful material on cable television.

The decision affirmed the panel of three federal district court judges that originally heard the case.

Section 505 required cable television providers whose offerings were “primarily dedicated to sexually-oriented programming” to restrict its availability to the hours of 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. The law sought to prevent children from viewing the channels through “signal bleed,” which occurs when nonsubscribers gain inadvertent access to audio or visual, or both, elements of the sexually explicit pay-per-view channels.

Playboy challenged section 505, arguing that this content-based restriction did not satisfy strict scrutiny. Playboy noted that section 504 of the act, the lockbox provision, provided a less restrictive alternative that would allow the government to regulate sexually-oriented programming without offending its First Amendment speech rights. In effect, each household had the option of making Playboy programming completely unavailable in that household.

In his opinion for the Court, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy affirmed the decision of the lower court and held that section 505 unconstitutionally curtailed not just Playboy’s First Amendment protection, but also that of willing viewers of the sexually oriented programming who wished to view it during times other than the designated window. Although conceding the presence of a compelling interest, Justice Kennedy cited section 504 as a less restrictive alternative, treating it as a per se indicator that section 505 was not narrowly tailored.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer dissented, taking issue with the majority’s contention that a less restrictive alternative existed. He identified the government interest in helping parents to protect their children from inadvertent exposure to indecent material as a compelling state interest, and read sections 504 and 505 together as a narrowly tailored means of achieving this.

Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent cited Ginzburg v. United States (1966) in support of his opinion that otherwise protected speech, such as the Playboy programming, which deliberately emphasized “sexually provocative aspects,” was proscribable. Because commercials airing on the Playboy channel advertised for the underlying nonobscene programming in an obscene way, the government was free to ban it entirely, leading Justice Scalia to conclude that section 505, a mere restriction, was constitutionally sound.

Justice Clarence Thomas concurred, emphasizing that the government could have prohibited the Playboy programming completely had it been deemed “obscene” within the meaning of Miller v. California (1973) rather than simply indecent.

Justice John Paul Stevens concurred, characterizing Ginzburg as “anachronistic” since it predated the Court’s recognition of First Amendment protection for commercial speech.

This article was written by James T. Gibson and published in 2009 when Mr. Gibson was staff counsel for the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.