The Bureau of Reclamation is best known for its great dams and powerplants. They stand astride the major rivers of the American West, monuments to a nation’s ingenuity and spirit of enterprise-–Hoover Dam on the Colorado River; Grand Coulee on the Columbia near Spokane, Washington; and Shasta Dam in California’s Sacramento River Valley. While these are among the most famous, they are only three of 475 dams maintained today by the Bureau of Reclamation, a unit of the U.S. Department of the Interior. While the dams give a face to the Bureau of Reclamation, it is the water stored behind them that goes to the heart of the Bureau’s core mission: managing, developing, and protecting water resources in the West.

Since 1902, the Bureau of Reclamation, or Reclamation in common usage, has played a central role in the settlement of the American West, a land so arid that parts of Nevada see fewer than 5 inches of rainfall a year. Irrigating the parched land was the earliest mission of the Bureau, established by the Reclamation Act of 1902. The act committed the Federal Government to construct permanent works--dams, reservoirs, and canals--to irrigate arid and semiarid lands in 16 western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). (Texas was added in 1906.) As the West has grown, so has Reclamation’s mission. Today, it is the West’s largest supplier of water and its largest producer of hydroelectric power, an agency truly “Managing Water in the West.”

Reclamation’s name comes from its original goal, to “reclaim” arid lands for human use by providing a secure, year-round supply of water. Water meant family farms, towns, and an economic base for the sparsely settled West. Without adequate rainfall, at least 20 inches a year, a farmer faced formidable odds against making the land productive. In fact, some would say the West begins where annual precipitation falls below the 20-inch mark. In the United States, that is the 100th meridian, an imaginary longitudinal line running through the heart of the Dakotas, south through Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, and then into Texas. On one side is the moist East; on the other, the arid West. The earliest mission of the Bureau of Reclamation (originally known as the U.S. Reclamation Service) was to make it possible for small farmers to make a go of it west of the 100th meridian.

The West is, indeed, arid, but that does not mean it has no water. Water flows in its streams and rivers, sometimes so mightily that a river such as the untamed Colorado could carve canyons, including the Grand Canyon. The fundamental challenge for Reclamation was not a lack of water, but how to divert the water from wild rivers, store it behind dams, and then deliver it, at the right time, to the farm lands that needed it. While most Western rivers run fast in the spring, their beds filling with snowmelt from the high country, by mid-summer they slow to a trickle in lower elevations, just when crops need the water the most. The Bureau of Reclamation solved the problem by constructing many dams, some of them the highest and largest dams in the world, storing water behind them, and then releasing it, as needed, to farmers and towns via canals, ditches, and aqueducts.

Reclamation was not the first to harness the West’s water. Even in prehistoric times, native peoples diverted streams to irrigate crops, and American settlers followed in the 19th century. In the 1870s and 1880s, hundreds of private irrigation companies tried to reclaim the West’s arid lands but, within 10 years, most had collapsed, brought down by a lack of know-how, profiteering, chaotic water laws, harsh weather, or the severe depression of the 1890s. Private efforts that did succeed proved it was possible to make the desert bloom, but large-scale projects presented great financial risk, making private capital hesitant to invest.

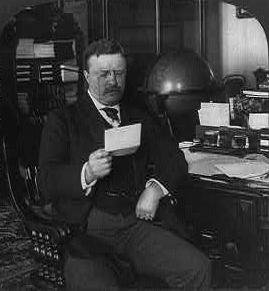

In Nevada, for instance, water advocate Francis G. Newlands launched the Truckee Irrigation Project, which he envisioned would create a “new” Nevada by irrigating the desert. Like so many other private projects, however, it fell flat, doomed by squabbling financiers and Nevada legislators. When Newlands became Nevada’s representative in Congress, he still believed in his dream for Nevada, but now he pushed for Federal help to make it come true. It was Newlands who introduced the bill that became the Reclamation Act of 1902, signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt the very day it landed on his desk.

The Reclamation Act established a special “reclamation fund,” intended to pay for construction of the dams and canals needed to irrigate the West. Money in the fund would come, not from the U.S. Treasury, but from the sale of public lands. People who developed farms on Reclamation projects were limited to 160 acres, required to reside on the property and use at least half of it for agriculture. A key provision stipulated that those using the water had to repay the government’s construction costs within 10 years.

Ambiguities in the Reclamation Act would entangle the Bureau in many legal questions, most often over where Federal authority ended and state or local authority began, but the great work of transforming the desert went forward with astonishing speed. Pioneer engineers went into the desert, recording stream flows, studying drainage basins, and deciding on the size of dams and reservoirs needed to support irrigated farms. Modern theories of dam building and structural analysis were still so new that engineers often had to develop and test new designs and methods along the way. By the end of 1907, the year the Reclamation Service gained independent status within the Department of the Interior, 20 projects had been authorized, at least one in each of the original 16 states, with the exception of Oklahoma. The Federal Government brought the necessary capital, engineering skills, and organizational structure that private enterprise was not able to provide, but needed to undertake the huge projects.

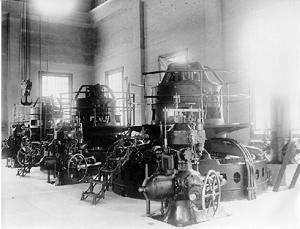

Over the years, details would change, but Reclamation’s general principles continued to center on a key provision that Federal monies spent on reclamation would be repaid by water users. As the years progressed and hydroelectric power became a benefit of key importance, users also paid for the electricity generated by Reclamation projects. Starting in 1909 with Theodore Roosevelt Dam near Phoenix and Minidoka Dam near Rupert, Idaho, Reclamation began using the massive power of falling water to generate electricity, but it wasn’t until 1928 that it embarked on huge, multiple purpose projects, the first of which was Hoover Dam, where hydroelectric power was a principal benefit. This followed an intense public debate on whether the Federal Government should become involved in public power production or whether that should be left to private enterprise. In 1939, Congress legitimized this new multi-purpose direction for the Bureau of Reclamation, whose future projects would address not only irrigation, but flood control, navigation, electric power, and municipal and industrial water supplies.

Thus, as the 1930s came to a close, Reclamation’s original mission under the 1902 Reclamation Act had expanded from just watering arid lands to multifaceted endeavors. Importantly, revenue generated from producing more hydroelectric power would be used to repay construction costs on ever larger and more expensive projects. In 1999, for example, revenues from hydroelectric generation at Grand Coulee Dam equaled about two-thirds of Reclamation’s entire appropriated budget.

Repaying government costs of construction had proved a sticky issue in Reclamation’s early years because many settlers were unable to meet the overly optimistic 10-year repayment period established under the Reclamation Act. In 1923, Congress dropped the 160-acre limit and revised the strict repayment structure for irrigation districts, giving them a long leash and even offering loans to give farmers the time and aid necessary to make their farms productive. A sign of things to come was authorization in 1928 of the Boulder Canyon Project, with Hoover Dam at its core. It was the first time large appropriations began to flow to Reclamation from U.S. general funds instead of the sale of public lands.

The Great Depression of the 1930s paved the way for some of Reclamation’s greatest achievements as the new administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt launched program after program in an attempt to spur the economy and provide jobs for out-of-work Americans by “priming the pump.” Unprecedented funds flowed to the Bureau of Reclamation as it became a key player in the New Deal’s Public Works Administration (PWA), which spent “big bucks on big projects,” such as building the Lincoln Tunnel, the causeway linking the Florida Keys to the mainland, and big dams, such as Grand Coulee, which stood as a monument to a prosperous future. Under the PWA, the Bureau of Reclamation undertook 37 projects; bringing the total number of authorized Reclamation projects by the outbreak of World War II to 68. Unlike the Works Progress Administration, which provided jobs for millions of the unemployed, the Public Works Administration was not a work-relief program, although its projects, which were put out for bid to private companies, helped keep people off relief. Unemployed young men, ages 18 to 24, did find work on Bureau of Reclamation projects through the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Thirty-four CCC camps were established on Reclamation sites, providing men to line canals with riprap to prevent erosion, clean drainage ditches, build roads and recreation amenities, and clear reservoir sites of brush and trees.

As great cities rose from the Western deserts during and after World War II, from Phoenix and Tucson to Las Vegas and Los Angeles, it was clear that the Bureau of Reclamation served the West far beyond its original rural vision. Today, Reclamation’s responsibilities extend not only to irrigating the arid West, but to generating hydroelectric power, delivering reliable and clean water supplies to municipalities and industries, regulating river flows for navigation, protecting lives and property from floods, and exploring ways to improve water quality and preserve wetlands and habitation for fish and wildlife. Reclamation’s huge reservoirs, from Lake Mead in Nevada to Belle Fourche in South Dakota, have created oases for outdoor recreation and extended Reclamation’s mission to working in partnership with non-profit organizations and cooperating groups such as Ducks Unlimited and the American Outdoors Association.

Today, as the West’s largest supplier of water and the largest wholesaler of water in the United States, the Bureau of Reclamation maintains 475 dams and 348 reservoirs with a total storage capacity of 245 million acre feet of water. (An acre foot equals about 326,000 gallons, enough to serve two average families for one year.) Reclamation projects bring water to more than 31 million people, and provide 140,000 farmers (one of every five in the West) with irrigation water for 10 million acres of farmland. Those lands produce 60 percent of the nation’s vegetables and 25 percent of its fruits and nuts. Reclamation also manages 289 recreation areas with a total of 350 campgrounds. As the largest producer of hydroelectric power in the American West, Reclamation has 58 power plants online, producing enough electricity to serve 3.5 million homes.

The Bureau’s expanded mission since its founding more than a century ago reflects today’s greater understanding of the complexities of water resource development. The Bureau has evolved into a contemporary water management agency with a mission not only “to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources” in the West, but to do it “in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public.” To accomplish this mission, Reclamation today works in partnership with state and Federal agencies, American Indian tribes, stakeholders, non-profit organizations and private groups to address and resolve issues. And, of course, engineering excellence remains integral to the Bureau, as it applies its expertise to projects big and small--from designing fish passageways and enhancing power grids, to monitoring older dams and employing technology to meet and balance competing needs in a world in which water is an ever-increasingly valuable resource.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.